[CAS2105.01-00] Introduction to Computing Research Course

HW3: Paper Blog Post

2024149002 Hyewon Nam

arXiv link: https://arxiv.org/abs/1409.4842#

In 2014, a team of researchers at Google introduced a convolutional neural network (CNN) architecture that significantly advanced computer vision performance.

In their paper “Going Deeper with Convolutions” (2014), the Google research team introduced GoogLeNet, a CNN that achieved state-of-the-art performance on the ImageNet Large-Scale Visual Recognition Challenge (ILSVRC).

The key idea behind this work was not simply making networks deeper, but making them deeper efficiently — maximizing representational power under a limited computational budget.

From Bigger Models to Smarter Architectures

Earlier CNNs such as AlexNet (2012) and VGGNet (2014) mainly improved accuracy by increasing the number of layers and filters.

This approach successfully expanded the network's capacity to learn complex patterns, but it also led to two critical problems:

1. Overfitting

When a model becomes too complex, it starts to memorize the training examples instead of learning general patterns. For example, it might perfectly classify the images it has seen during training, but fail on new, unseen ones — just like a student who remembers every practice question but can’t solve a new test problem!

2. Computation cost

The number of operations in convolutional layers grows roughly with the square of the number of filters, making the model slow and expensive. For instance, doubling the number of filters roughly quadruples the computation needed for one layer.

The GoogLeNet team asked a crucial question:

💡 "Can we build a deeper network without increasing computational cost proportionally?"

From Fully Connected to Sparse Connections — A Theoretical Insight

To answer that, the authors turned to theory.

They referenced Arora et al. (2013), who showed that if we could identify neurons that frequently activate together, we could cluster them and connect only within those groups — creating a sparse network topology.

In such a sparse network, each neuron doesn't need to connect to every neuron in the next layer.

Instead, it only connects to those that share similar activation patterns — just like how neurons in the visual cortex respond selectively to certain spatial patterns or orientations.

In other words, not all information paths are equally useful — most of the meaningful computation happens in a small subset of connections.

This idea is elegant but impractical on modern hardware.

GPUs are optimized for dense matrix operations, not for handling arbitrary sparse connections.

True sparse architectures, although theoretically efficient, are slow in practice due to memory access inefficiency.

So the GoogLeNet team asked:

💡 "How can we approximate the benefits of sparse connectivity while keeping the efficiency of dense computation?"

Their answer became the Inception module — a practical realization of this “sparse-to-dense” idea.

Bridging the Gap: Approximating Sparsity with Dense Components

The authors realized they could approximate the effect of sparse connectivity while keeping computations dense and hardware-friendly. Instead of trying to hard-code sparse links, they designed a modular block — the Inception module — that captures multiple levels of abstraction.

Images contain information at multiple spatial scales — small edges, mid-level textures, and large-scale shapes.

Traditional CNNs apply a fixed filter size (e.g., 3 × 3) per layer, meaning they can only extract features of one scale at a time.

The Inception module breaks this limitation by applying multiple convolutional filters of different sizes in parallel:

- 1 × 1 convolution: captures local correlations across channels (essentially per-pixel feature mixing).

- 3 × 3 convolution: detects medium-sized features like corners or object parts.

- 5 × 5 convolution: captures large spatial patterns such as object outlines.

- Pooling path: summarizes local regions, providing translation invariance.

🔎 What is translation invariance?

Translation invariance refers to a CNN’s ability to produce the same feature response even when the input image is shifted in position. In other words, it means that the model can recognize an object even if it moves slightly within the image. Pooling layers help achieve this by summarizing nearby activations, making the model less sensitive to exact spatial location.

The outputs of these parallel branches are concatenated along the depth dimension, forming a unified feature map that integrates multi-scale representations.

This structure allows the model to simultaneously consider fine and coarse visual details — something traditional sequential CNN layers couldn’t do efficiently.

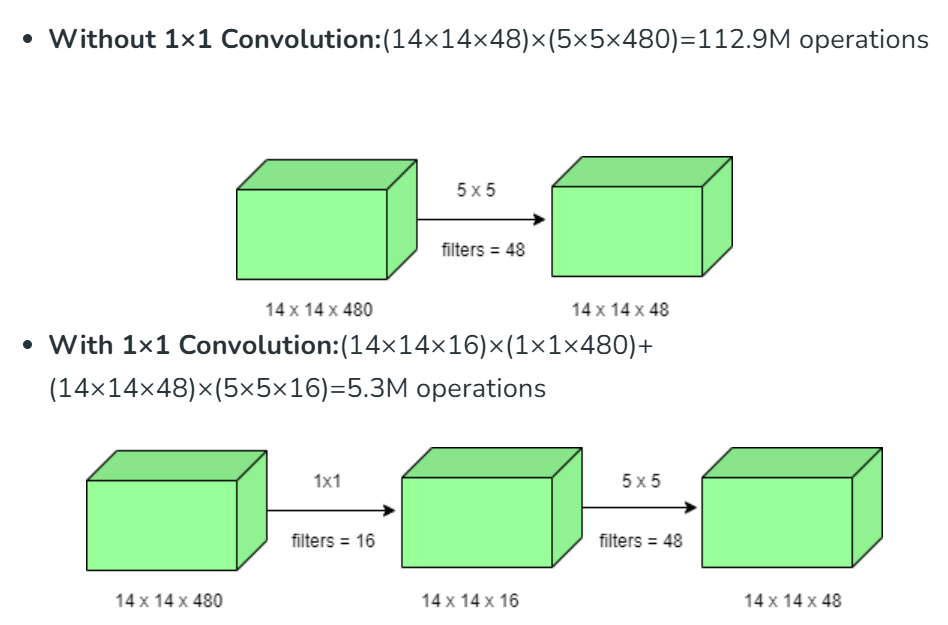

The Computational Challenge and the Role of 1 × 1 Convolution

At first glance, the Inception idea seems expensive.

Applying 3 × 3 and 5 × 5 convolutions directly on a high-dimensional feature map can lead to a massive number of parameters and floating-point operations.

To solve this, the authors introduced a dimension reduction strategy using 1 × 1 convolutions.

This layer acts as a bottleneck that reduces the number of input channels before expensive convolutions.

Formally, if an input feature map has $C_{in}$ channels and we apply $N$ filters of size $k$ × $k$, the computational cost is proportional to $k^2$ × $C_{in}$ × $N$. By first applying a 1 × 1 convolution to reduce $C_{in}$ to a smaller $C'_{in}$, the subsequent cost becomes $k^2$ × $C'_{in}$ × $N$, where $C'_{in} < C_{in}$.

This leads to a substantial reduction in both parameters and computation.

In practice, the 1 × 1 convolution also adds nonlinearity (via ReLU activation),

enabling the network to learn more abstract transformations and still remain efficient.

This concept of "reduce before expensive convolution" became one of the core design patterns of modern CNNs.

Building GoogLeNet: Deep but Efficient

By stacking multiple Inception modules, the authors built GoogLeNet, a 22-layer-deep CNN (27 layers including pooling).

Unlike previous architectures that used fully connected layers at the end, GoogLeNet replaced them with average pooling layers before the final classifier (conceptually equivalent to what is now known as Global Average Pooling), reducing parameters and improving generalization.

🔎 What is Global Average Pooling?

Global Average Pooling (GAP) replaces fully connected layers at the end of a CNN. It averages each feature map into a single value per channel — for example, a 10×10×32 feature map becomes a 32-dimensional vector. This drastically reduces parameters, lowers overfitting risk, and improves efficiency.

The model also introduced auxiliary classifiers — small side networks attached to intermediate layers — which provided extra gradient signals during training.

These auxiliary heads acted as regularizers and helped mitigate the vanishing gradient problem in training such a deep architecture.

🔎 What is the vanishing gradient problem?

In deep networks, gradients can shrink as they are backpropagated through many layers, making early layers learn very slowly or not at all. To solve this, auxiliary classifiers inject additional loss signals during training. These provide stronger gradient flow to earlier layers, preventing overfitting while stabilizing deep training.

Despite its depth, GoogLeNet contained only about 5 million parameters, compared to 60 million in AlexNet — roughly 12 × fewer — yet it achieved significantly higher accuracy.

Experimental Results

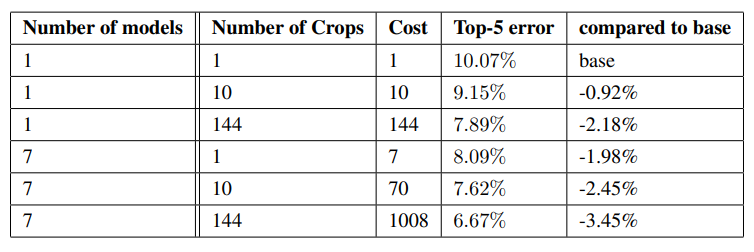

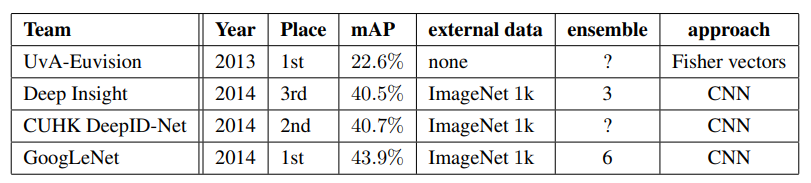

GoogLeNet was evaluated in the ImageNet Large Scale Visual Recognition Challenge (ILSVRC) 2014, a large-scale competition for image classification and object detection.

📚 Dataset & Training Method

Both the classification and detection experiments were conducted on ImageNet (ILSVRC 2014),

but the two tasks used slightly different subsets of the data:

- Classification: ~1.2 M training images, 50 K validation, and 100 K test images across 1 000 categories (each image has one label).

- Detection: 200 object classes with bounding-box annotations, allowing multiple objects per image.

Both models were trained using asynchronous stochastic gradient descent (SGD) with 0.9 momentum,

a 4 % learning-rate decay every 8 epochs, and extensive data augmentation

(random cropping, color and aspect-ratio variation, and interpolation changes).

The detection task additionally used the Inception network as the region classifier within an R-CNN-style pipeline.

🔎 What is R-CNN?

R-CNN (Regions with CNNs), proposed by Girshick et al. (2014), detects objects in two steps:

(1) generate region proposals using low-level cues like color or texture, and

(2) run a CNN classifier on each region to label what object it contains.

GoogLeNet’s detection system followed this idea but enhanced it with MultiBox proposals and the Inception network for higher accuracy.

📏 Evaluation Metrics

Performance was measured by:

- Top-1 accuracy – correct label = top prediction

- Top-5 error rate – correct label among top five guesses (official ranking metric)

- For detection: mean Average Precision (mAP) with IoU ≥ 50%

🏆 Results

- Classification: 6.67% Top-5 error (1st place), without using external data

- Detection: 43.9% mAP (1st place) using an Inception-based R-CNN approach

- Demonstrated that architectural innovation and efficient design can outperform mere model scaling.

From GoogLeNet to Modern CNNs

The Inception architecture marked a turning point in CNN design.

It introduced the principle of multi-scale processing and efficient computation, influencing later architectures such as:

- Inception-v2/v3: improved normalization and factorization.

- ResNet: introduced identity shortcuts to preserve gradient flow.

- EfficientNet: formalized the idea of compound scaling (depth, width, resolution).

In summary, "Going Deeper with Convolutions" showed that a network's success depends not only on how large it is, but on how intelligently its computation is distributed.

The combination of structural elegance and computational efficiency made GoogLeNet one of the foundational architectures in modern deep learning.

GoogLeNet’s structure demonstrated how organized computation can outperform brute-force depth — an idea that continues in modern models like ResNet and Vision Transformers.

For readers interested in this evolution, exploring how later architectures refined Inception’s principles would be a good next step! 🚀

🔗 References

[1] Szegedy, C., Liu, W., Jia, Y., et al. “Going Deeper with Convolutions.” arXiv:1409.4842(2014). https://arxiv.org/abs/1409.4842

[2] https://blog.csdn.net/COINVK/article/details/128995633

[3] https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/machine-learning/understanding-googlenet-model-cnn-architecture/

[4] https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Global-average-pooling-layer-replacing-the-fully-connected-layers-The-output-layer_fig10_318277197

[5] Guo, Z., Chen, Q., Wu, G., Xu, Y., Shibasaki, R., & Shao, X. (2017). Village building identification based on ensemble convolutional neural networks. Sensors, 17(11), 2487. https://doi.org/10.3390/s17112487